Living with Uncertainty

And embracing the chaos of life

This post comes from a keynote I will give today on how we have evolved to deal with uncertainty and why we need new ways to find our center.

The Problem with Waiting

Houston Airport had a problem.

Passengers were complaining about the wait time for baggage. They solved the problem with the obvious solution - hiring more baggage handlers to get the bags onto the carousel faster. The wait time was reduced to an average of eight minutes, which is well within industry standards. But the complaints continued.

It took passengers one minute to walk to the baggage claim and a seven-minute wait for their bags. Houston airport flipped the experience. They moved the arrival gate to be farther away so passengers would walk for 7 minutes and wait for one minute. After this, the complaints virtually disappeared.

This counterintuitive solution reveals something fundamental about human nature. The problem wasn't the waiting itself, it was the experience of not knowing how long they were going to wait for.

Something similar happened on London's Underground when they implemented a countdown system in 2001.

Simply displaying when the next train would arrive decreased passenger stress dramatically, even though the actual waiting times hadn't changed at all. What causes anxiety, it turns out, isn't the duration of a wait but the uncertainty within it.

Standing at a baggage carousel and watching an empty belt spin creates the same psychological tension as staring down an empty train tunnel, wondering if your train will arrive in one minute or ten.

This insight about uncertainty and information helped London transform their passenger experience, just as it helped Houston's airport solve its baggage claim problem.

When we're walking to claim our bags, even if the journey takes longer, we feel a sense of agency. We're not just waiting; we're progressing. We can see our movement, feel it in our steps, and measure it in the distance covered.

Similarly, when Underground passengers can see "Next train: 4 minutes," they can mentally prepare, and use the time to read or send a message. The uncertainty transforms into a defined space they can work with.

When Uncertainty Gets Personal

This pattern of how uncertainty shapes our behavior isn't abstract - it plays out in deeply personal ways. I remember working with a sales leader who discovered something about himself one sleepless morning.

His company sent out daily sales reports at 4 AM, and that particular morning, having woken up unusually early, he checked his phone and found disappointing numbers. The surge of adrenaline was immediate, driving him out of bed and straight to work, determined to correct course.

But what began as a random early morning check transformed into something more profound. Soon his body, without an alarm, would wake him at 4 AM every day, as if he had developed an internal clock synchronized to the arrival of those numbers.

The reports became more than data - they became the script for his day. Poor numbers meant an immediate start to work; good numbers granted permission for more rest. In this tiny window between 4 AM and dawn, you could see the whole story of his relationship with uncertainty playing out: the need to know, the physical response to information, the illusion of control that comes from immediate action.

Like the Underground passengers checking the countdown clock, or the airport travelers pacing toward baggage claim, he had developed a coping mechanism for uncertainty. But unlike walking to baggage claim, which has a clear endpoint, this pattern had no natural conclusion - it was a loop that repeated each morning, shaping not just his days but gradually transforming his relationship with both work and rest.

These aren't just random behaviors or individual quirks - they're manifestations of our fundamental relationship with uncertainty. Just as London Underground passengers felt more at ease simply knowing when their train would arrive, we seek out information, any information, to fill the uncomfortable void of not knowing. The challenge isn't that we seek information - it's that in today's world, the seeking itself can become compulsive, a reflexive response to the slightest hint of uncertainty.

Our Ancient Relationship with the Unknown

This response is deeply woven into our evolutionary story. As sociologist Edward O. Wilson observed, we have "Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god-like technologies." To understand why we check our phones hundreds of times a day, we need to understand how our ancestors handled their own uncertainties.

They developed two competing systems: a threat-detection system that made them hyper-aware of potential dangers, and a learning system that rewarded them for exploring and understanding their environment.

But their most powerful technology for managing uncertainty wasn't either of these systems - it was storytelling. In communal gatherings, there were stories that explained everything from the changing of seasons to the movements of stars. These weren't just entertainment; they were a way to make sense of an unpredictable world.

Consider how many ancient cultures have flood myths, or stories about why the sun rises and sets. Whether or not these stories were factually accurate wasn't the point - they provided something more valuable: a framework for understanding, a way to place uncertainty within a larger pattern of meaning.

Modern Solutions, Ancient Problems

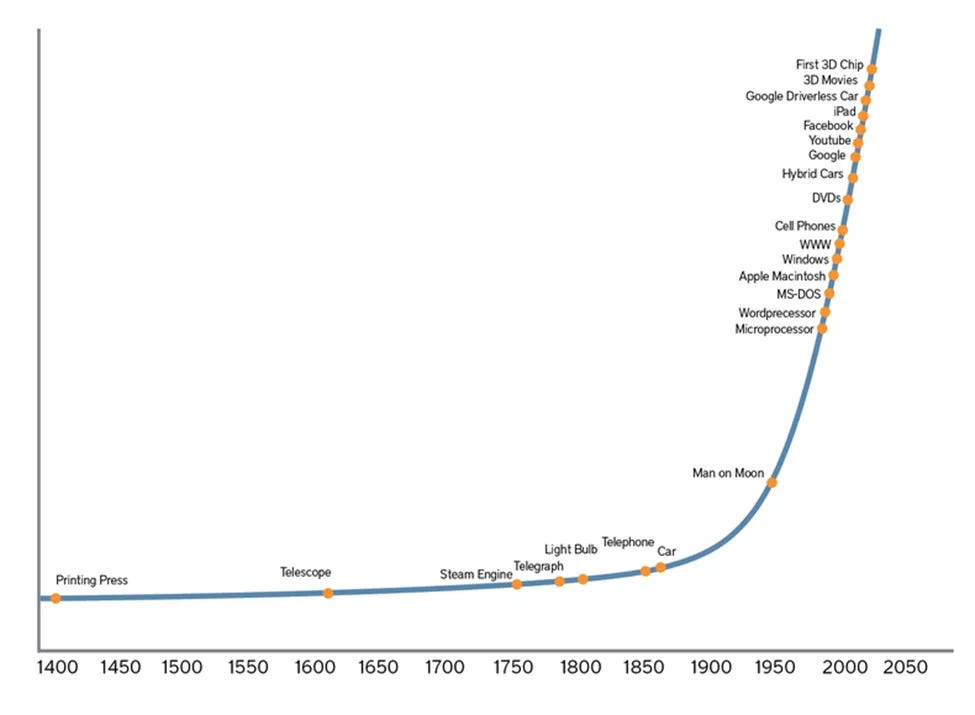

Today, we have unprecedented access to knowledge about our world - a development that should, in theory, reduce our uncertainty. We understand weather patterns our ancestors attributed to temperamental gods. We can track diseases they might have seen as curses. We can predict celestial events they wove elaborate myths around. Yet this explosion of information hasn't necessarily led to greater peace of mind.

Consider one of today's most popular podcasts, "Diary of a CEO," which draws millions of listeners per episode. Where our ancestors might have gathered to hear a single, coherent narrative about life's mysteries, modern listeners encounter a weekly rotation of experts offering isolated fragments of certainty. One episode features a toxicologist warning about everyday products affecting fertility, another presents a body language expert revealing the secret codes of human connection, while a third brings in a life coach sharing techniques for anxiety reduction. Each expert speaks with authority, each offers valuable insights, but together they create a blur of competing certainties.

This pattern repeats across our information landscape. We no longer have myths about spirits causing illness; instead, we have endless studies about what might make us sick, each adding new items to our mental checklist of things to fear. We've replaced stories about fate and destiny with countless frameworks for self-optimization, each promising to give us control over our future. The ancient tale of a hero's journey has been replaced by thousands of success stories, each suggesting a different path to follow.

This wealth of information provides knowledge but not necessarily wisdom. Our ancestors' stories, though simpler and often factually incorrect, provided something our modern information streams struggle to deliver: coherence. They offered a complete worldview, a way to understand how all the pieces fit together.

Our modern predicament isn't just about having too much information - it's about the loss of narrative coherence. We consume these fragments of expertise like snacks, temporarily satisfying our hunger for certainty but never quite providing the nourishment of a complete meal. It's why we can listen to hundreds of hours of expert advice and still feel uncertain about basic life decisions. It's why we can know more than ever about the world and still feel lost within it.

This helps explain our compulsive information-seeking behaviors. Just as our ancestors might have sought comfort in retelling familiar stories, we repeatedly check our devices, listen to more podcasts, read more articles, hoping that the next piece of information will finally help everything make sense. We're seeking not just knowledge but resolution - that satisfying sense of completion that comes at the end of a well-told story.

Yet life, as we know, rarely provides such neat resolutions. The challenge we face isn't to find the perfect story or the ultimate expert opinion, but to develop a different relationship with uncertainty itself. Perhaps what we need isn't more information about how to control our world, but better ways to live meaningfully within its inherent uncertainty.

When Systems Take Over

Here's the thing about uncertainty - it doesn't just mess with our heads as individuals. It shapes how entire companies and organizations behave, often in surprisingly similar ways. A fascinating book by Dan Davies called "The Unaccountability Machine" points out something I can't stop noticing now: organizations build what he calls "accountability sinks" - basically, systems that make it impossible to find anyone actually responsible for decisions.

You know that feeling when you're stuck in an automated phone menu, being bounced from option to option, never quite reaching a human who can actually help? That's an accountability sink in action. It's not a flaw in the system - it's exactly how it's meant to work. The system is designed to handle problems without anyone having to take personal responsibility for them.

Let's go back to our sales leader waking up at 4 AM to check his numbers. He's not alone in this behavior - entire organizations do a version of the same thing. They create more reports, gather more data, add more metrics. Not because they need more information to make decisions, but because gathering data feels like doing something. It's like corporate-level phone checking - it gives us the illusion of control without actually making things better.

What makes this really interesting is how these systems feed themselves. A company might start out with good intentions - "Let's create a new reporting system to make things more transparent!" But instead of making things clearer, they often end up building what Davies calls an "unaccountability machine" - a system so complicated that it becomes impossible to figure out who's actually making decisions. It's like trying to find out who's responsible for a mistake in a huge company and everyone keeps pointing to someone else.

Just as we comfort ourselves by checking our phones, organizations comfort themselves by creating systems that look like they're in control. The London Underground got it right with their countdown clocks, and Houston Airport nailed it by giving people a longer walk - they worked with how people actually behave. But most organizational systems do the opposite. They try to remove human judgment entirely, thinking this will create certainty. Instead, they just push the uncertainty into the shadows.

This explains something that's always puzzled me: why do we often feel less confident the more information we have? Whether it's someone binge-listening to expert advice on podcasts or a company drowning in market data, the problem isn't that we don't have enough information. The problem is our relationship with uncertainty itself. We've built these elaborate systems promising to eliminate uncertainty through data and standardization, but in doing so, we've actually made it harder to use good judgment and take real responsibility.

Finding Stability in a World of Change

We live in an extraordinary time. The technology we have access to would seem like magic to our ancestors. We can connect with anyone across the globe instantly. We can access the world's knowledge from a device in our pocket. We can watch events unfold in real-time from anywhere on the planet.

But every evolutionary leap in our external environment demands an internal adaptation. As our world grows more complex and interconnected, we need new ways to maintain our stability within it.

The ancient Greeks built labyrinths - not to get lost in, but to find their way to the center. Indian culture created mandalas, circular designs that always lead back to a central point. Modern physics shows us the same pattern - in the eye of a storm or the still point of a spinning wheel, there's always a quiet center amid chaos.

These aren't just historical curiosities. Across cultures and times, humans have recognized the importance of finding and maintaining access to their center. But our era might be the first where this skill has become essential rather than optional.

Without a strong connection to our center, we risk being overwhelmed by the very technologies meant to empower us. Each new advancement, each new stream of information, each new possibility can become another source of destabilization rather than opportunity.

But with this skill - this ability to find and maintain our center - we can move differently through our rapidly changing world. We can embrace the magic of our technological age while maintaining our internal coherence. We can engage with the complexity around us without losing ourselves within it.

These ancient practices are pointing to something both timeless and urgently relevant: we can't eliminate uncertainty, but we can develop a different relationship with it. One that allows us to remain steady as we engage with all the possibilities our modern world offers.

Over the past few years, I've been exploring and developing practices that help me stay centered in this fast-moving world. They've changed how I work, how I rest, and how I engage with technology. This year, I'll be sharing what I've learned - not as universal solutions, but as possibilities for finding your own way to move with the complexity of our time.

Excellent insight. And I do hope that you will share more about the practices that you have found to stay centered in our chaotic, modern existence.