We're Not Distracted - We're Hyper-Focused

And that's the problem.

Among the ancient stories that continue to speak to us, few feel as modern as the tale of Narcissus, the boy whose reflection became his world.

The story begins with a prophecy. His mother, Liriope, feared what would become of her beautiful child. She sought the oracle Tiresias and asked what every parent asks in some form: Will my son live a long life?

“Yes,” Tiresias replied, “so long as he never knows himself.”

For sixteen years, Narcissus moved through the world untouched by fate. He was radiant, admired, and distant. Those who loved him found their affection reflected back and never reciprocated.

Among them was Echo, a nymph cursed to repeat only the last words she heard. When she first saw Narcissus hunting in the forest, she followed him silently, unable to speak her love. At last, she revealed herself, and he recoiled, rejecting her with a cold indifference that pierced her to the core.

Humiliated, Echo withdrew into the woods. Her body wasted away until only her voice remained, repeating the words of others but never her own.

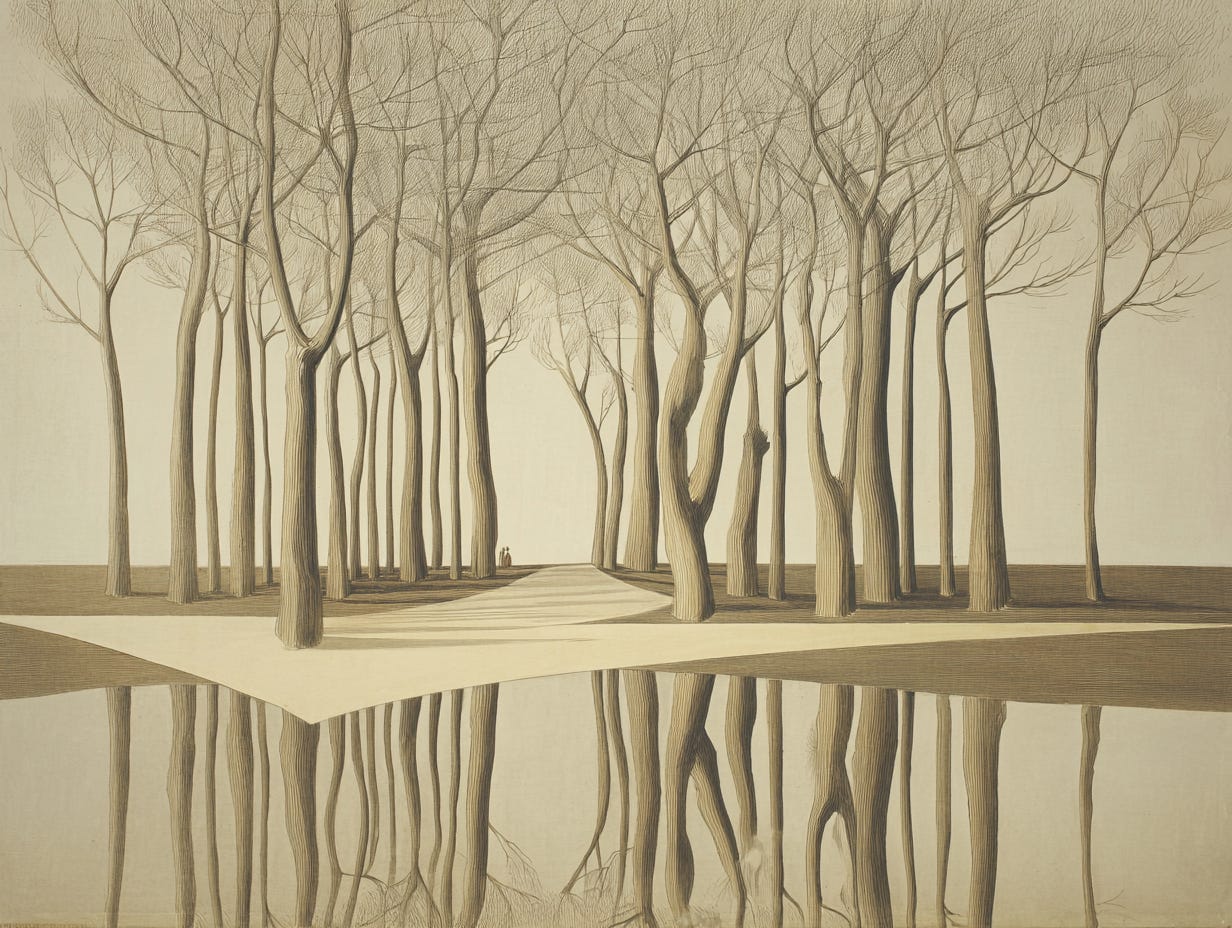

It was after this encounter, wandering deeper into the forest, that Narcissus came upon a still pool. He bent to drink, and in the water saw a face so exquisite he could not look away.

Each time he reached to touch it, the surface broke, the image dissolved, and he was left staring into ripples that revealed nothing but his own movement. So he held still, drinking not from the water but from the sight before him.

Time slowed, then stopped. The forest, the air, even the sound of the river withdrew.

Unable to touch what he saw, unable to look away, he wasted away by the water’s edge.

So consumed by his reflection, he lost the world.

The Shape of a Gaze

Every age reshapes the human eye.

The plow bent our gaze toward the ground.

The book trained it to move in lines.

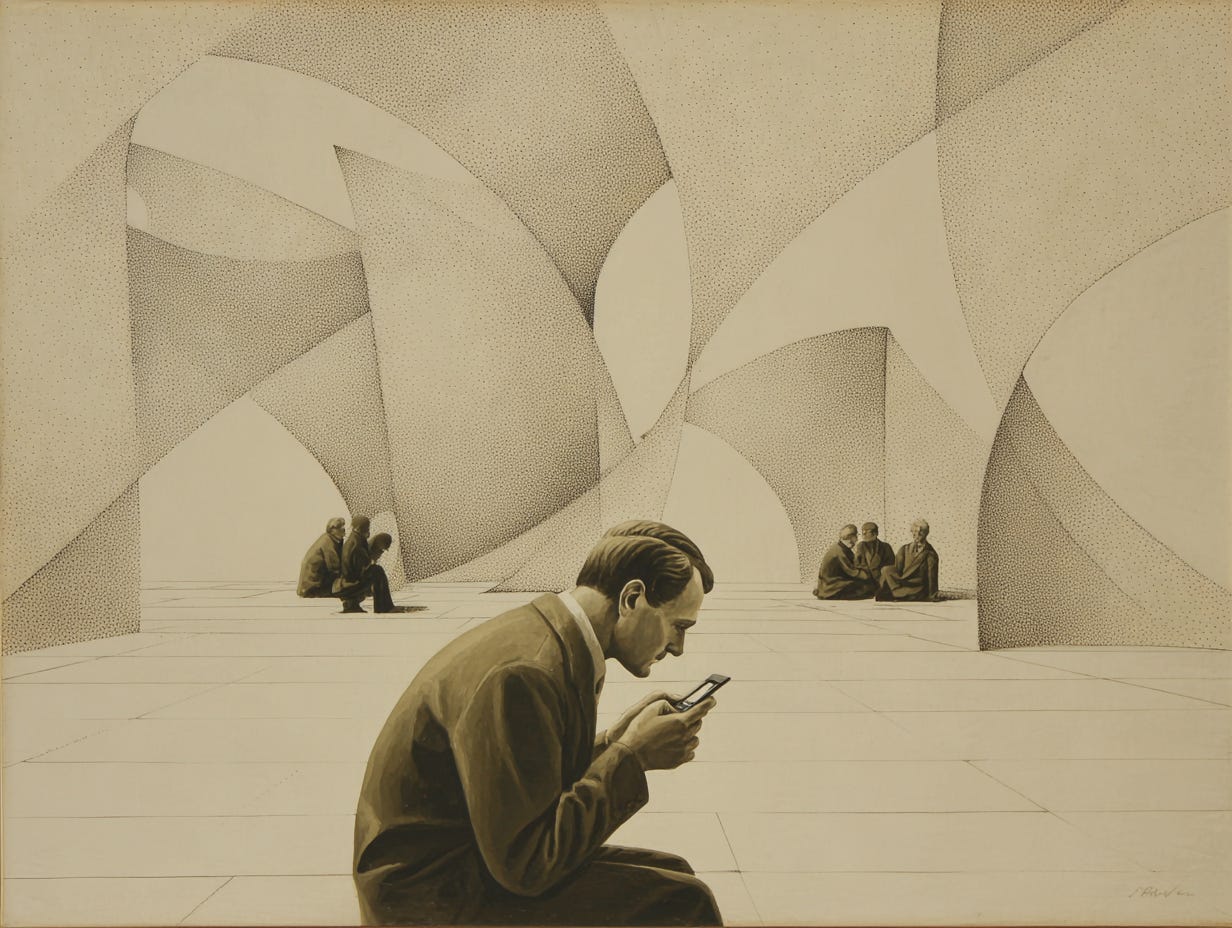

The screen teaches us to stare.

Marshall McLuhan once said, “We shape our tools, and afterward, our tools shape us.”

It’s a simple truth that’s easy to overlook. We think we’re choosing what to look at, but the tools we use are quietly deciding how we look.

Science is now beginning to show how literal that is.

Eye specialists describe a condition called digital eye strain, a mix of blurred vision, headaches, and tension that comes from long hours of screen use. The main cause is something known as near work: the act of keeping our eyes focused on something close for long periods.

To do this, the small focusing muscles inside the eye must stay slightly tensed, while both eyes turn inward to keep a single image clear. Without breaks, this system can get stuck in a state of strain. Researchers call it accommodative fatigue, the eye’s version of being overworked.

Extended close-up work keeps the focusing muscles active even after you stop looking, creating a lingering sense of visual effort and tension. That lingering activation means the eyes don’t fully relax. The visual system remains half-engaged, as if waiting for the next task.

During normal conversation, we blink about 18–22 times per minute. On screens, that number drops to 4–6.

Blinking might seem trivial, but it’s one of the clearest signs of how attention changes the body. We blink more when we feel relaxed and socially engaged; we blink less when we’re fixated or under strain. The less we blink, the drier the eyes become, and the longer we stay locked in narrow focus.

This pattern doesn’t stop at the eyes. When our vision stays close and tight, the head tilts forward, the neck and shoulders stiffen, and the upper back rounds. Doctors now treat these as part of one system: the visual posture of modern life. Common complaints like neck pain, headaches, and light sensitivity all trace back to this same posture of focus.

There are simple ways to interrupt it. The same research that identified this cycle also confirmed a small but powerful reset known as the 20-20-20 rule: every twenty minutes, look at something at least twenty feet away for twenty seconds. It gives the eyes a chance to relax, restores moisture, and tells the body it can ease out of vigilance.

What the research makes clear is that our way of seeing has become conditioned into a single mode of readiness. The body holds that stance long after the screen goes dark. Over time, this habit of near-focus doesn’t just shape how our eyes work; it begins to shape how we move, feel, and think.

Trapped in the Spotlight

We often talk about distraction as if it were the problem, as if we’ve lost the ability to focus. But what we call distraction may actually be something else. It may be the symptom of a system that has forgotten how to come down. A body that stays wired for action even when there’s nothing to fight or chase.

A vigilant nervous system cannot sustain focus. It was never designed to. It is built to track, to scan for danger, to shift from one point of attention to the next in search of what might go wrong. The same mechanism that once kept our ancestors alive now keeps us locked in a state of activation.

This is why so many people feel both overstimulated and unfocused at once. Our attention isn’t absent; it’s trapped. We live in a state of hyper-focus, the kind that narrows and jumps but never settles. It feels like concentration, but it’s closer to vigilance. The mind and the gaze are both confined to the near field, pulled toward the next signal, the next stimulus, the next demand.

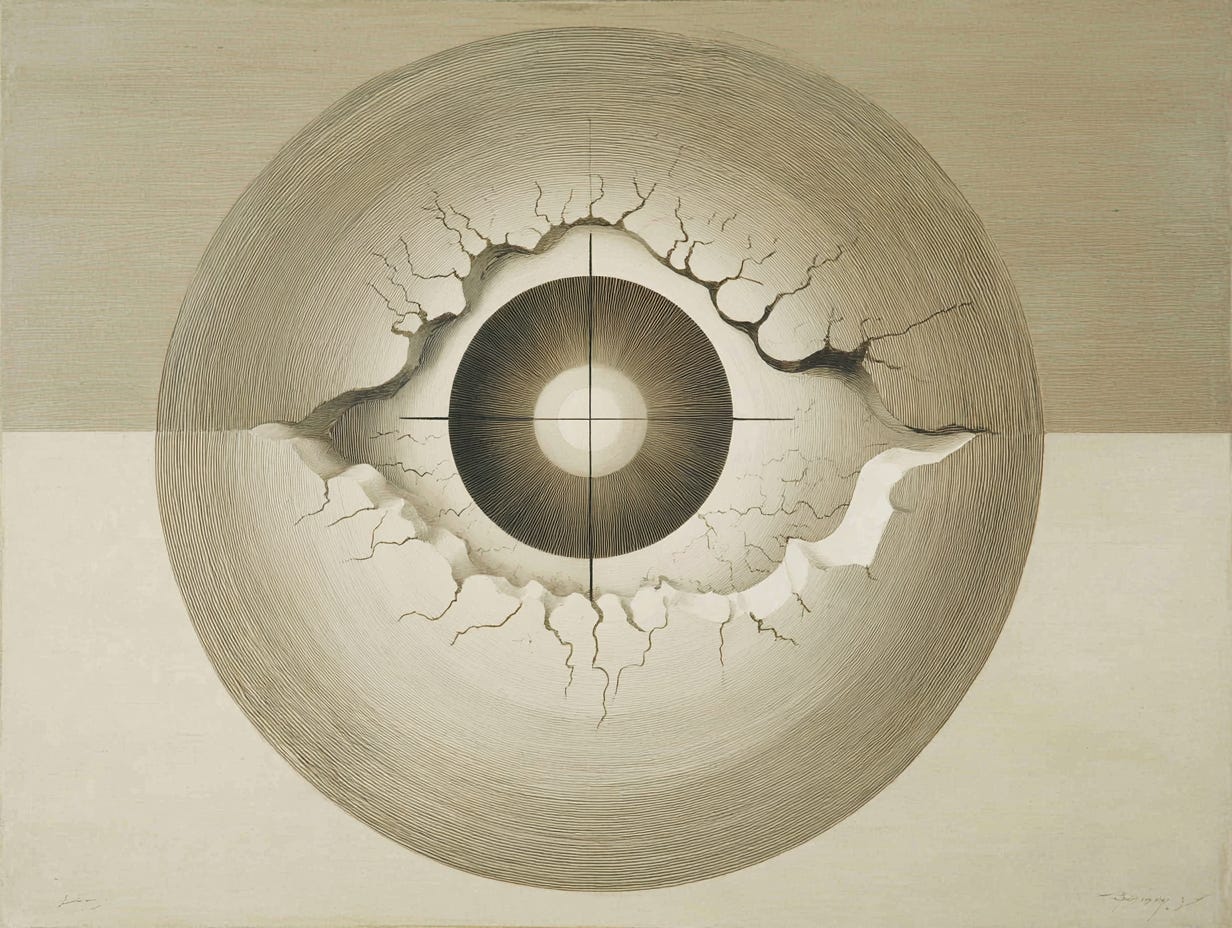

The philosopher of attention James Williams describes three kinds of attention: the spotlight, the starlight, and the daylight.

The spotlight is narrow and precise. It is the kind of attention we use to perform a task or respond to something immediate.

The starlight is slower. It’s the kind that orients us toward what matters, the goals and values that give our life meaning.

Daylight is awareness itself, the clarity that allows us to step back and see where our attention is being drawn.

Modern life trains us to live almost entirely in the spotlight. Every ping, headline, and notification pulls us toward what is immediate. We mistake this for being distracted, but it’s really a kind of hyper-focus.

The longer we stay here, the more we lose access to the other lights that help us navigate. Without starlight, there is no sense of direction, only motion. Without daylight, there is no reflection, only reaction.

When our eyes stay fixed on what’s near, our thoughts begin to follow the same pattern. We start to think in fragments. We see what’s in front of us but lose the thread that connects it to the whole. Meaning depends on that thread. Without it, life becomes a series of isolated moments that never quite add up.

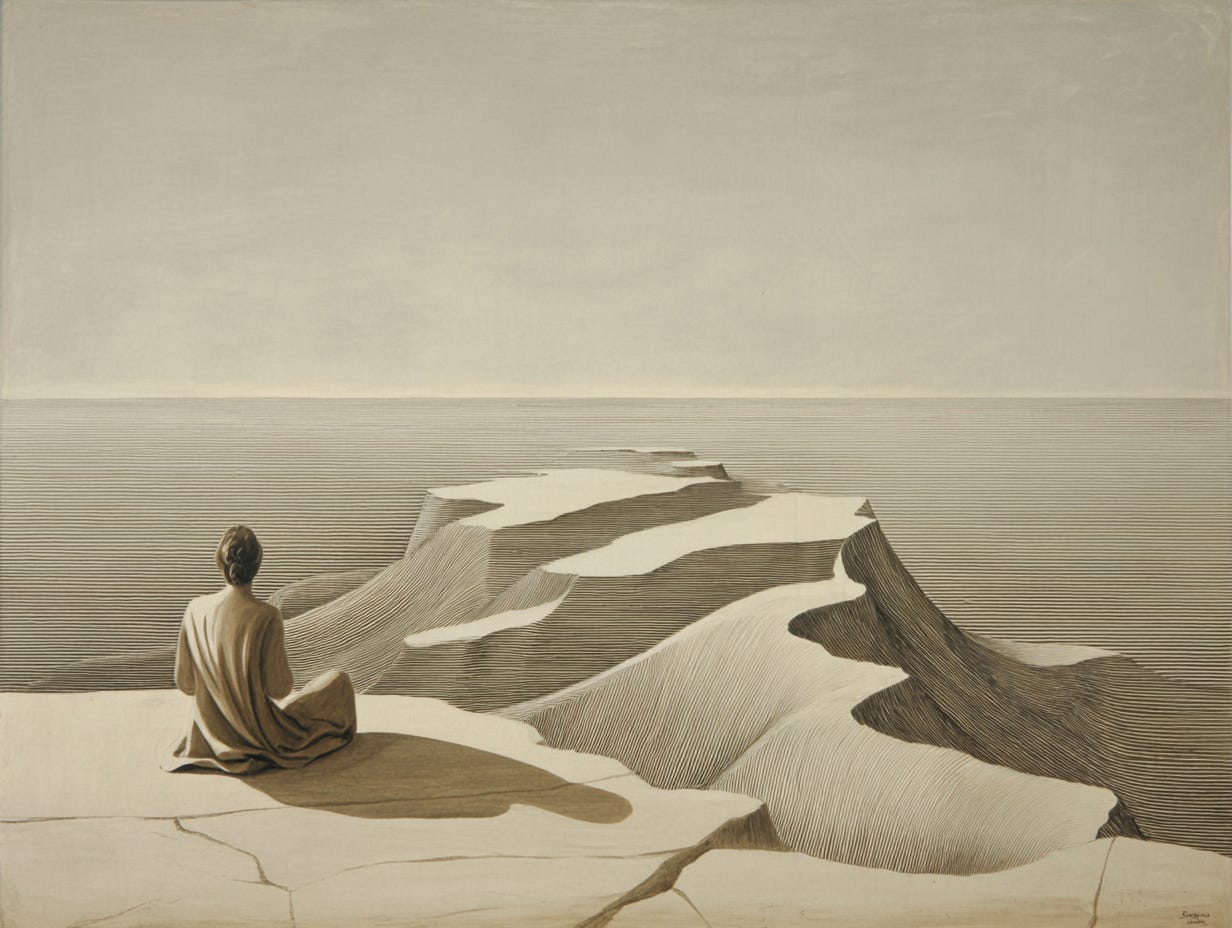

To recover that thread, we don’t need to force more focus. We need to widen our view. To let the gaze soften and, with it, the mind. When the body feels safe, attention naturally expands. It begins to move again, to alternate between precision and perspective. And in that movement, coherence starts to return.

Vigilance is the Culture

Neuroscience now affirms what contemplative traditions have long understood: the body’s internal state determines the mind’s capacity for awareness. When the nervous system feels safe, the body relaxes. Breathing deepens, muscles release, and vision naturally widens.

In that state, we can see how one thing connects to another, how context gives meaning to what stands in front of us. When we feel safe, the mind can hold complexity. It can live in uncertainty without collapsing into anxiety or judgment.

When that safety fades, the opposite happens. The body tightens, the pupils narrow, and attention contracts around whatever feels most immediate. The brain starts filtering for what’s urgent or potentially threatening, and in doing so, it stops noticing the background.

Stephen Porges calls this process neuroception, the body’s quiet, unconscious scanning of the world for signs of safety or danger. It happens before thought, but it shapes what thought becomes possible. When the body is on alert, we can’t think widely. Our ideas begin to mirror our gaze: narrow, repetitive, and defensive.

A culture that lives in that state of subtle vigilance not only moves quickly; it begins to think differently. It grows reactive. It values activity over understanding. It measures life by how much is produced rather than by what is felt or understood. Conversations shrink, not because there’s less to say, but because the tempo of life allows less room to listen.

The economic historian Harold Innis once wrote that civilizations rise or fall according to how they balance time and space. This is the balancing act of preserving memory and reaching outward toward progress. Some societies are shaped by time, keeping meaning alive through continuity and tradition. Others are shaped by space, by the expansion of communication, and the speed of connection.

In our time, expansion has overtaken endurance. We have reach, but little retention. The present moment dominates, refreshed endlessly but rarely absorbed.

When a culture loses its sense of duration, life begins to feel like a chase. Each new thing replaces the one before it. The past feels irrelevant, and the future feels perpetually behind schedule. What remains is an endless present, filled with motion but thin in meaning.

Derek Thompson recently described this shift in his essay Everything Is Television. He argues that every medium, from the printed page to social media to AI image generators, is slowly being pulled toward a single attractor: the flow of continuous video. Drawing on Raymond Williams’s term from 1974, Thompson explains that television transformed culture by replacing discrete, bounded works with a constant stream of imagery. Today’s platforms perfect that logic. On Instagram or TikTok, no single video matters. It’s the flow itself that holds our attention.

The result is that meaning is no longer expected to cohere. Each fragment of content can be watched, half-watched, or ignored, because coherence isn’t the point. What matters is motion, the feeling of being carried by an unending stream. Thompson calls this “casual viewing,” but it extends far beyond television. It is the perceptual rhythm of a civilization that has lost the thread of continuity, that no longer expects experience to add up to anything larger than itself.

When perception fragments in this way, coherence becomes optional. We stop expecting things to make sense because our nervous systems are trained to move on before sense can form. The pace of media has become a mirror of our own physiology: restless, vigilant, unable to pause.

A culture that cannot hold time will always feel like it is running out of it. And when we live in that constant acceleration, imagination contracts. We lose the capacity to sense continuity between past and future, self and other, human and environment. The spaces between things, the ones that give relationships their texture, begin to disappear.

To see the world whole again, we need to restore the inner conditions that allow the body, and therefore the mind, to widen its view. When the gaze softens, perception follows. And when perception expands, coherence returns. The fragments don’t need to vanish; they simply need to find their place within the larger pattern of life.

How Connection Breaks Down

The psychiatrist Bruce Perry discovered a pattern in how people recover from stress and trauma that has stayed with me. In his work with traumatized children, he noticed that healing follows a particular sequence: first, we regulate, then we relate, and only then can we reason. These three phases are not steps to rush through, but a rhythm to follow.

Regulation comes first because safety is what makes connection possible. When the body settles, the mind can open. Only then can we relate—to listen, to attune, to feel another person’s presence. From there, reasoning becomes possible, the kind of thinking that doesn’t rush to conclusion but grows out of shared understanding.

In my work with teams, I see imbalance between these three stages all the time. When communication breaks down, it’s rarely due to lack of intelligence or intent. More often, it’s because someone is trying to be heard before the other person has the capacity to listen. One person comes in ready to communicate something important, but the person on the receiving end is already overwhelmed or emotionally flooded. They’re not connected, and the message can’t land. The words might be clear, but the meaning is lost in the disconnection.

I also see this principle in action through my work with an improv school here in Santa Fe that I’m part of. It’s remarkable to have a space where people can practice what it means to truly relate to one another. Before any practice or show, the group begins by tuning into each other through games that involve watching and responding. These exercises aren’t about performance. They’re about attunement and feeling the group as one organism rather than a collection of individuals.

Those who struggle with improv share a common pattern: they’re not listening. They’re caught in the effort to plan, to get it right, to make something happen. Their attention is fixed on their next move rather than what’s unfolding in front of them. They’re focused on serving themselves rather than discovering what best serves the collective moment. But as they begin to let go and trust, something shifts. They stop forcing and start responding. The scenes flow, and the comedy that follows isn’t about cleverness; it’s about surprise.

To an outside observer, improv might look like chaos, but there’s actually deep structure beneath it. Every scene begins with what’s called a base reality: the shared understanding of where we are, who we are, and what’s happening. From that foundation, the unusual and surprising can emerge. This same principle exists in every form of healthy relationship or collaboration. When there’s a base reality, we can move freely. When it’s missing, chaos takes its place.

This is something I see not only on stage but in everyday life. Last week a client scheduled a call with me while she was at a conference. We spoke during her lunch break. I know what those environments are like. The constant stimulation, the demand to network, the feeling of being “on” all day while trying to manage everything else. When she joined the call, I could hear the tension in her voice. Rather than diving straight into the work, we spent ten minutes on simple exercises to relax the eyes and slow the breath. Only then did we begin.

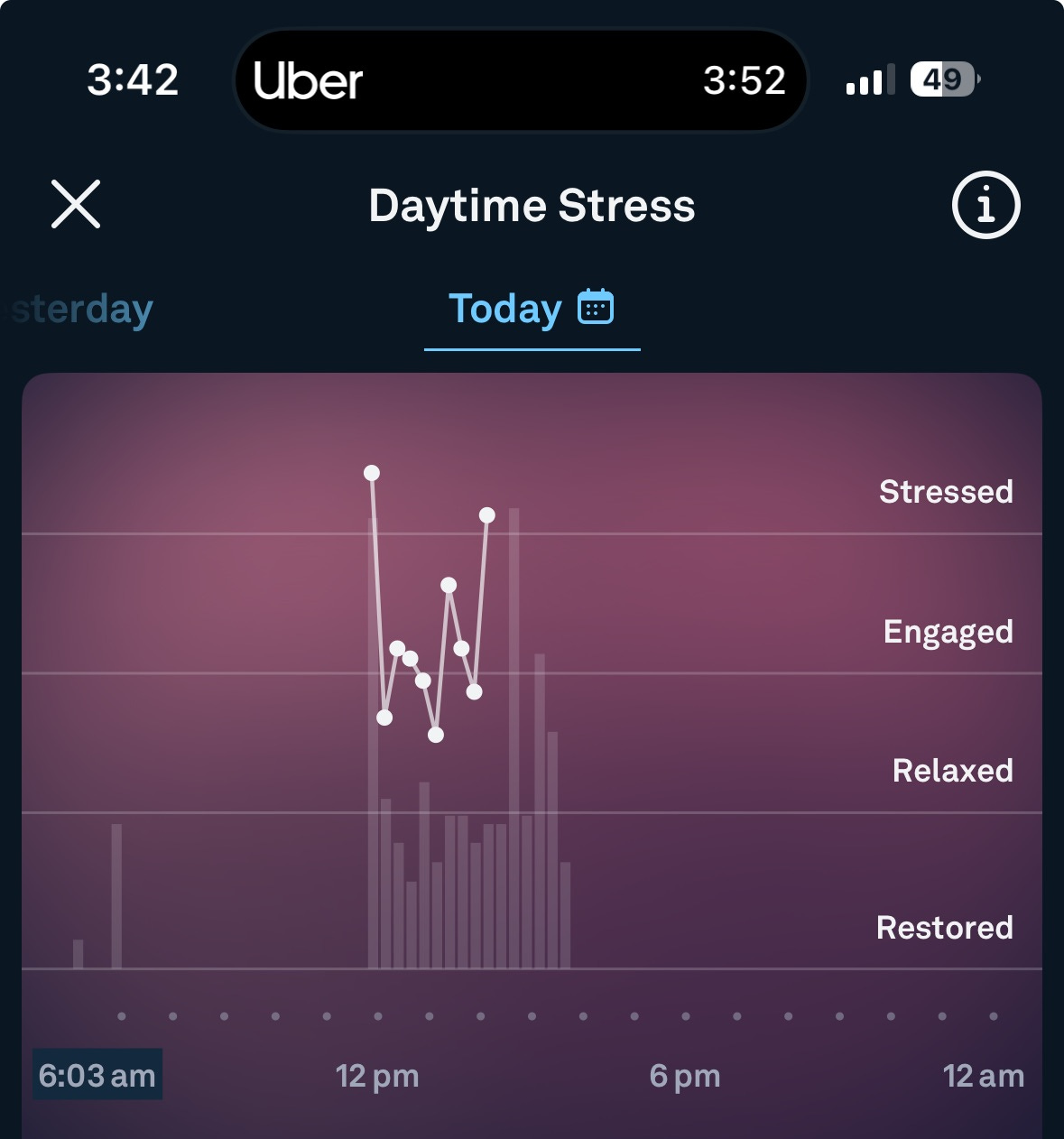

After the call, she sent me a screenshot from her Oura ring showing how her stress levels had dropped sharply during those few minutes. She moved from a state of vigilance to a state of engagement. Regulation isn’t about staying calm; it’s about restoring movement. It’s the ability to shift between states, to rise and fall without getting stuck.

This sequence: regulate, relate, reason, is the antidote to the fixation that defines so much of modern life. It reminds us that coherence begins in the body, not the mind. When our gaze is tight and our nervous systems are overstimulated, we lose the foundation for connection.

Many of the distances we feel from one another today aren’t just digital. They live in our bodies. Even face-to-face, we can sense how far away people feel. It’s true that algorithms and echo chambers have divided us, but the gap often begins closer to home.

Many of us use our phones as pacifiers, small devices we turn to for comfort or calm. But they rarely calm us. The same tools that promise regulation often keep our systems subtly activated. The eyes stay fixed, the breath stays shallow, and the body remains half-ready. We scroll to relax, but the act itself keeps us from settling.

Practicing a Wider View

Everything you’ve read so far leads back here, to the body.

Our eyes, breath, and attention are not abstract ideas. They are the way we meet the world. When we reconnect with them, even for a few minutes, something softens. The noise quiets. The world becomes whole again.

If you’d like to experience this directly, I’ve recorded a short guided meditation. It’s an eight-minute practice to release tension in the eyes and reset the body. You can do it anywhere: between meetings, at your desk, or before bed.

The meditation begins by grounding through contact, bringing awareness to the hands, feet, and breath. Then it guides you through gentle exercises that help release tension around the eyes and allow them to move freely again. These movements signal to the body that it can rest, that the vigilance can ease.

You can listen to it whenever you need a pause, when your focus begins to tighten, or when you notice fatigue setting in. It’s a simple way to widen your view again.

→ Listen to the 8-minute meditation here.

This idea of all media pointing to a constant flow of video is worth contemplating more. Thanks for sharing.

"Those who struggle with improv share a common pattern: they’re not listening. They’re caught in the effort to plan, to get it right, to make something happen. Their attention is fixed on their next move rather than what’s unfolding in front of them. They’re focused on serving themselves rather than discovering what best serves the collective moment."

Interesting realization - when I coach clients on sales, they struggle with the exact same thing. They're so focused on what to say next that they miss what's right in front of them.